The global water crisis also involves water pollution. For water to be useful for drinking and irrigation, it must not be polluted beyond certain thresholds. According to the World Health Organization, in 2008, approximately 880 million people (or 13% of the world population) did not have access to safe drinking water. At the same time, about 2.6 billion people (or 40% of the world’s population) lived without improved sanitation, defined as having access to a public sewage system, septic tank, or even a simple pit latrine. Approximately 1.7 million people die yearly from diarrheal diseases associated with unsafe drinking water, inadequate sanitation, and poor hygiene. Almost all of these deaths are in developing countries, and around 90% occur among children under the age of 5 (Figure 1). Compounding the water crisis is the issue of social justice; poor people more commonly lack clean water and sanitation than wealthy people in similar areas. Globally, improving water safety, sanitation, and hygiene could prevent up to 9% of all diseases and 6% of all deaths.

In addition to the global waterborne disease crisis, chemical pollution from agriculture, industry, cities, and mining threatens global water quality. Some chemical pollutants have serious and well-known health effects, whereas others have poorly known long-term health effects. In the U.S., more than 40,000 water bodies currently fit the “impaired ” definition set by the EPA, which means they could neither support a healthy ecosystem nor meet water quality standards. In Gallup public polls conducted over the past decade, Americans consistently put water pollution and water supply as the top environmental concerns over air pollution, deforestation, species extinction, and global warming.

Any natural water contains dissolved chemicals, some of which are important human nutrients, while others can harm human health. The concentration of a water pollutant is commonly given in very small units such as parts per million (ppm) or even parts per billion (ppb). An arsenic concentration of 1 ppm means 1 part of arsenic per million parts of water. This is equivalent to one drop of arsenic in 50 liters of water. To give you a different perspective on appreciating small concentration units, converting one ppm to length units is 1 cm (0.4 in) in 10 km (6 miles), and converting one ppm to time units is 30 seconds in a year. Total dissolved solids (TDS) represent the total amount of dissolved material in water. Average TDS values for rainwater, river water, and seawater are about four ppm, 120 ppm, and 35,000 ppm, respectively.

Water Pollution Overview

Water pollution is water contamination by an excess amount of a substance that can cause harm to human beings and/or the ecosystem. The level of water pollution depends on the abundance of the pollutant, the ecological impact of the pollutant, and the use of the water. Pollutants are derived from biological, chemical, or physical processes. Although natural processes such as volcanic eruptions or evaporation sometimes can cause water pollution, most pollution is derived from human, land-based activities (Figure 2). Water pollutants can move through different water reservoirs as the water carries them through stages of the water cycle (Figure 3). Water residence time (the average time a water molecule spends in a water reservoir) is very important to pollution problems because it affects pollution potential. Water in rivers has a relatively short residence time, so pollution usually is there only briefly. Of course, river pollution may simply move to another reservoir, such as the ocean, where it can cause further problems. Groundwater is typically characterized by slow flow and longer residence time, which can make groundwater pollution particularly problematic. Finally, pollution residence time can be much greater than the water residence time because a pollutant may be taken up for a long time within the ecosystem or absorbed into the sediment.

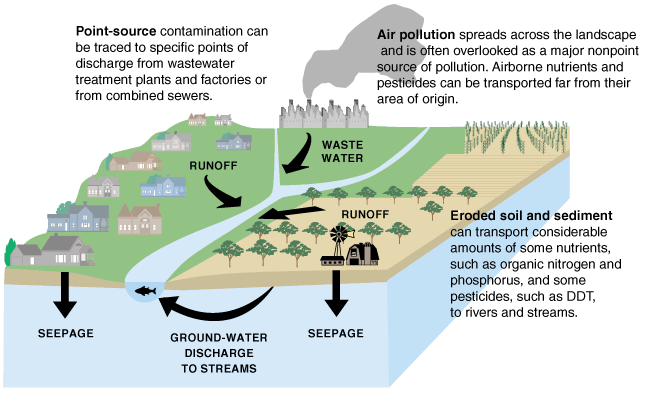

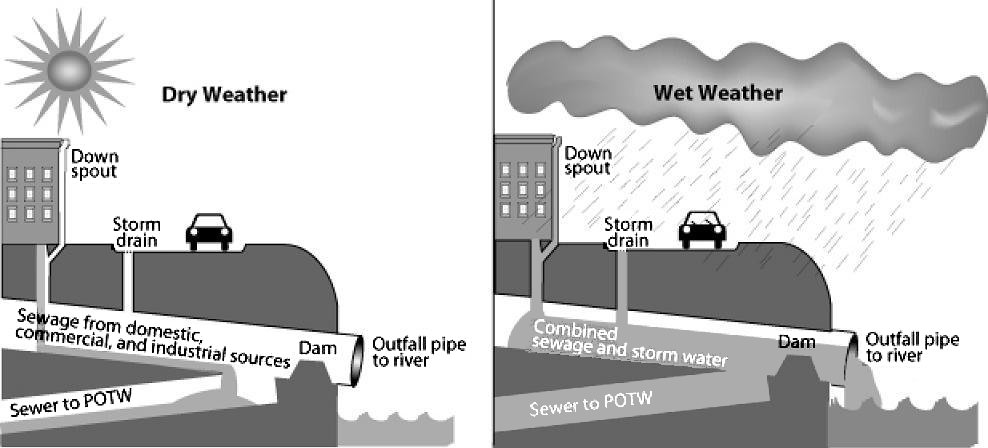

Pollutants enter water supplies from point sources, which are readily identifiable and relatively small locations, or nonpoint sources, which are large and more diffuse areas. Point sources of pollution include animal factory farms (Figure 4) that raise a large number and high density of livestock such as cows, pigs, and chickens. Also included are pipes from factories or sewage treatment plants. Combined sewer systems with single underground pipes to collect sewage and stormwater runoff from streets for wastewater treatment can be a major source of pollutants. During heavy rain, stormwater runoff may exceed sewer capacity, causing it to back up and spill untreated sewage directly into surface waters (Figure 5).

Nonpoint sources of pollution include agricultural fields, cities, and abandoned mines. Rainfall runs over the land and through the ground, picking up pollutants such as herbicides, pesticides, and fertilizer from agricultural fields and lawns; oil, antifreeze, animal waste, and road salt from urban areas; and acid and toxic elements from abandoned mines. Then, this pollution is carried into surface water bodies and groundwater. Nonpoint source pollution, which is the leading cause of water pollution in the U.S., is usually much more difficult and expensive to control than point source pollution because of its low concentration, multiple sources, and much greater volume of water.

Types of Water Pollutants

Oxygen-demanding waste is an extremely important pollutant to ecosystems. Most surface water in contact with the atmosphere has a small amount of dissolved oxygen, which aquatic organisms need for cellular respiration. Bacteria decompose dead organic matter and remove dissolved oxygen (O2) according to the following reaction:

organic matter + O2→CO2 + H2O

Too much decaying organic matter in water is a pollutant because it removes oxygen from water, which can kill fish, shellfish, and aquatic insects. The amount of oxygen used by aerobic (in the presence of oxygen) bacterial decomposition of organic matter is called biochemical oxygen demand (BOD). The major source of dead organic matter in many natural waters is sewage, whereas grass and leaves are minor sources. An unpolluted water body, concerning BOD, might be a turbulent river flowing through a natural forest. Turbulence continually brings water in contact with the atmosphere, where the O2 content is restored. The dissolved oxygen content in such a river might range from 10 to 14 ppm O2, and BOD is low, which supports clean-water fish such as trout. A polluted water body with high BOD might be a stagnant lake in an urban setting with pollution from sewage runoff. This results in a high input of organic carbon and has limited opportunities for water circulation and contact with the atmosphere. In such a lake, the dissolved O2 content is typically ≤5 ppm O2, BOD is high, and low O2-tolerant fish, such as carp and catfish, dominate.

Excessive plant nutrients, particularly nitrogen (N) and phosphorous (P), are pollutants closely related to oxygen-demanding waste. Aquatic plants require about 15 nutrients for growth, most of which are plentiful in water. N and P are called limiting nutrients, however, because they usually are present in water at low concentrations, restricting the total amount of plant growth. This explains why N and P are major ingredients in most fertilizers. High concentrations of N and P from human sources (mostly agricultural and urban runoff, including fertilizer, sewage, and phosphorus-based detergent) can cause cultural eutrophication, which leads to the rapid growth of aquatic producers, particularly algae (Figure 6). Thick mats of floating algae or rooted plants lead to water pollution, damaging the ecosystem by clogging fish gills and blocking sunlight. A small percentage of algal species produce toxins that can kill animals, including humans. Exponential growths of these algae are called harmful algal blooms. When the prolific algal layer dies, it becomes oxygen-demanding waste, creating very low O2 concentrations in the water (< 2 ppm O2), a condition called hypoxia. This results in a dead zone because it causes death from asphyxiation to organisms that cannot leave that environment. An estimated 50% of North America, Europe, and Asia lakes are negatively impacted by cultural eutrophication. In addition, the size and number of marine hypoxic zones have grown dramatically over the past 50 years, including a very large dead zone located offshore Louisiana in the Gulf of Mexico. Cultural eutrophication and hypoxia are difficult to combat because they are caused primarily by nonpoint source pollution, which is difficult to regulate, and N and P, which are difficult to remove from wastewater.

Pathogens are disease-causing microorganisms, e.g., viruses, bacteria, parasitic worms, and protozoa, which cause various intestinal diseases such as dysentery, typhoid fever, and cholera. Pathogens are the major cause of the water pollution crisis discussed at the beginning of this section. Unfortunately, nearly a billion people worldwide are exposed to waterborne pathogen pollution daily, and around 1.5 million children, mainly in underdeveloped countries, die yearly of waterborne diseases from pathogens. Pathogens enter water primarily from human and animal fecal waste due to inadequate sewage treatment. In many underdeveloped countries, sewage is discharged into local waters either untreated or after only rudimentary treatment. In developed countries, untreated sewage discharge can occur from overflows of combined sewer systems, poorly managed livestock factory farms, and leaky or broken sewage collection systems. Water with pathogens can be remediated by adding chlorine or ozone, by boiling, or by treating sewage in the first place.

Oil spills are another kind of organic pollution. Oil spills can result from supertanker accidents such as the Exxon Valdez in 1989, which spilled 10 million gallons of oil into the rich ecosystem of coastal Alaska and killed massive numbers of animals. The largest marine oil spill was the Deepwater Horizon disaster, which began with a natural gas explosion (Figure 7) at an oil well 65 km offshore of Louisiana and flowed for 3 months in 2010, releasing an estimated 200 million gallons of oil. The worst oil spill ever occurred during the Persian Gulf War of 1991, when Iraq deliberately dumped approximately 200 million gallons of oil in offshore Kuwait and set more than 700 oil well fires that released enormous clouds of smoke and acid rain for over nine months.

During an oil spill on water, oil floats to the surface because it is less dense than water, and the lightest hydrocarbons evaporate, decreasing the spill’s size but polluting the air. Then, bacteria decompose the remaining oil in a process that can take many years. After several months only about 15% of the original volume may remain, but it is in thick asphalt lumps, a form that is particularly harmful to birds, fish, and shellfish. Cleanup operations can include skimmer ships that vacuum oil from the water surface (effective only for small spills), controlled burning (works only in early stages before the light, ignitable part evaporates but also pollutes the air), dispersants (detergents that break up oil to accelerate its decomposition, but some dispersants may be toxic to the ecosystem), and bioremediation (adding microorganisms that specialize in quickly decomposing oil, but this can disrupt the natural ecosystem).

Toxic chemicals involve many kinds and sources, primarily from industry and mining. General kinds of toxic chemicals include hazardous chemicals and persistent organic pollutants that include DDT (pesticide), dioxin (herbicide by-product), and PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls, which were used as liquid insulators in electric transformers). Persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are long-lived in the environment, biomagnified through the food chain, and can be toxic. Another category of toxic chemicals includes radioactive materials such as cesium, iodine, uranium, and radon gas, which can result in long-term exposure to radioactivity if it gets into the body. A final group of toxic chemicals is heavy metals such as lead, mercury, arsenic, cadmium, and chromium, which can accumulate through the food chain. Heavy metals are commonly produced by industry and at metallic ore mines. Arsenic and mercury are discussed in more detail below.

Arsenic (As) has been famous as an agent of death for many centuries. Only recently have scientists recognized that health problems can be caused by drinking small arsenic concentrations in water over a long time. It enters the water supply naturally from weathering arsenic-rich minerals and human activities such as burning coal and smelting metallic ores. The worst case of arsenic poisoning occurred in Bangladesh’s densely populated, impoverished country, which had experienced 100,000s deaths from diarrhea and cholera each year from drinking surface water contaminated with pathogens due to improper sewage treatment. In the 1970s, the United Nations provided aid for millions of shallow water wells, dramatically dropping pathogenic diseases. Unfortunately, many of the wells produced water naturally rich in arsenic. Tragically, an estimated 77 million people (about half of the population) inadvertently may have been exposed to toxic levels of arsenic in Bangladesh as a result. The World Health Organization has called it the largest mass poisoning of a population in history.

Mercury (Hg) is used in various electrical products, such as dry cell batteries, fluorescent light bulbs, and switches, as well as in manufacturing paint, paper, vinyl chloride, and fungicides. Mercury acts on the central nervous system and can cause loss of sight, feeling, hearing, nervousness, shakiness, and death. Like arsenic, mercury enters the water supply naturally from weathering of mercury-rich minerals and from human activities such as coal burning and metal processing. Mercury concentrates in the food chain, especially in fish, in a process caused by biomagnification (Figure 8). It acts on the central nervous system and can cause loss of sight, feeling, and hearing, as well as nervousness, shakiness, and death. Like arsenic, mercury naturally enters the water supply from weathering Hg-rich minerals and from human activities such as coal burning and metal processing. A famous mercury poisoning case in Minamata, Japan, involved methylmercury-rich industrial discharge that caused high Hg levels in fish. People in the local fishing villages ate fish up to three times per day for over 30 years, which resulted in over 2,000 deaths. During that time, the responsible company and national government did little to mitigate, help alleviate, or even acknowledge the problem.

Biomagnification represents the processes in an ecosystem that cause greater chemical concentrations, such as methylmercury, in organisms higher up the food chain. Mercury and methylmercury are present in only very small concentrations in seawater; however, algae absorb methylmercury at the base of the food chain. Then, small sh eat the algae, large sh and other organisms higher in the food chain eat the small sh, and so on. Fish and other aquatic organisms absorb methylmercury rapidly but eliminate it slowly from the body. Therefore, each step up the food chain increases the concentration from the step below. Largemouth bass can concentrate methylmercury up to 10 million times over the water concentration, and fish-eating birds can concentrate it even higher. Other chemicals that exhibit biomagnification are DDT, PCBs, and arsenic.

Hard water contains abundant calcium and magnesium, which reduces its ability to develop soapsuds and enhances scale (calcium and magnesium carbonate minerals) formation on hot water equipment. Water softeners remove calcium and magnesium, which allows the water to lather easily and resist scale formation. Hard water develops naturally from dissolved calcium and magnesium carbonate minerals in soil; it does not negatively affect people.

Groundwater pollution can occur from underground sources, and all pollution sources contaminate surface waters. Common sources of groundwater pollution are leaking underground storage tanks for fuel, septic tanks, agricultural activity, landfills, and fossil fuel extraction. Common groundwater pollutants include nitrate, pesticides, volatile organic compounds, and petroleum products. Another troublesome feature of groundwater pollution is that small amounts of certain pollutants, e.g., petroleum products and organic solvents, can contaminate large areas. In Denver, Colorado, 80 liters of several organic solvents contaminated 4.5 trillion liters of groundwater and produced a five km-long contaminant plume. A major threat to groundwater quality is from underground fuel storage tanks. Fuel tanks are commonly stored underground at gas stations to reduce explosion hazards. Before 1988 in the U.S., these storage tanks could be made of metal, which can corrode, leak, and quickly contaminate local groundwater. Now, leak detectors are required, and the metal storage tanks are supposed to be protected from corrosion or replaced with fiberglass tanks. There are around 600,000 underground fuel storage tanks in the U.S., and over 30% still do not comply with EPA regulations regarding release prevention or leak detection.