Frame 4: Research as Inquiry

William Perrenod

Inquiry is another word for curiosity or questioning. Maybe a better title for this concept is “Research as Curiosity,” because it more accurately captures the way our human brains work.

Inquiring Minds Want to Know

When you think to yourself, “How old is Madonna?” and you google it to find out her age, that’s research! You had a question (how old is Madonna?), you applied a search strategy (googling “Madonna age”) and you found an answer to the question. That’s it! A question and finding an answer, that’s research.

But it’s not all research can be. Even after your research question is answered, you may still remain curious and go back to the inquiry step again and ask another question and seek another answer about your topic. Sometimes we’re never really done even though we’ve answered the initial question and maybe even written a research paper on the topic. If it’s a topic you’re really interested in, you will keep asking and answering questions again and again.

If you’re really curious about Madonna, you might think to yourself:

How old is Madonna? Wait, really? Her skin looks amazing! What’s her skincare routine? Seriously, what year was she born? WOW! She wrote children’s books! Does my local public library have any of her books?

In this example, your questions lead you to answers which, when you’re really interested in a topic, lead you to more and more questions. Humans are naturally curious; we have an instinct to learn things and that drives us to ask questions. It’s all “Research as Inquiry.”

Identifying an Information Need

One of the tricky parts of Research as Inquiry is determining a situation’s information need. It sounds simple to ask yourself, “What information do I need?” and sometimes we do it unconsciously. But it’s not always easy. Here are a few examples of information needs:

- You need to know what your niece’s favorite Paw Patrol character is so you can buy her a birthday present. Your research is texting your 8-year-old sister. Your sister texts back “Everest”, and your research is done. You buy the present and turn into a rock star at the birthday party. Your information need was a short answer based on your sister’s opinion.

- You’re trying to convince a friend on Facebook that Nazis are bad. You compile a list of opinion pieces from credible news publications like the Wall Street Journal and the New York Times, gather first-hand narratives of Holocaust survivors and victims of hate crimes, and find articles that debunk eugenics. Your information need isn’t scholarly publications, it’s information and personal confirmations you identify on the Internet. It’s information a person might read in their free time, information that isn’t too difficult to understand, and doesn’t require access to an expensive library database.

- Your college professor assigned an eight-page research paper. You decide to research oceanography. Since you really don’t know much about oceanography, you google “oceanography” and begin reading information on that topic. Since this is a broad topic, you decide to narrow your research to a related topic you identified: ocean heat content. Armed with the information you found on the Internet you then write a thesis statement that sums up what the central point of your research paper will be. Your thesis statement might look like this:

The rising sea level is a current threat to our shorelines and the result of climate change.

To support this thesis statement’s assertion, you would have to find information on how changes in the ocean heat play an important role in sea levels rising; how ocean heat contributes to global warming and the links between ocean heat and hurricanes. Lastly, because this is a college research paper, you professor wants you to reference authoritative information in your paper. This means you will search for relevant scholarly articles accessible from your library’s databases.

Sometimes it helps to break down big information needs into smaller ones. Look at the last example above: You’re writing a research paper. What are the smaller parts?

- Information Need 1: Find some information related to the broad topic: oceanography.

- Information Need 2: Find some information that will help you narrow your topic.

- Information Need 3: Find relevant scholarly articles on your topic.

It’s easier to break your information need into smaller steps and accomplish them one at a time. And it highlights an important part of the research process that’s surprisingly difficult to learn: ASK QUESTIONS. You can’t write a research paper if you don’t understand the instructions, so ask. You can’t write a research paper if you don’t know how to find scholarly articles, so ask. The quickest way to learn is to ask questions.

The Takeaway

- When you have a question, ask it.

- When you’re genuinely interested in something, keep asking questions and finding answers.

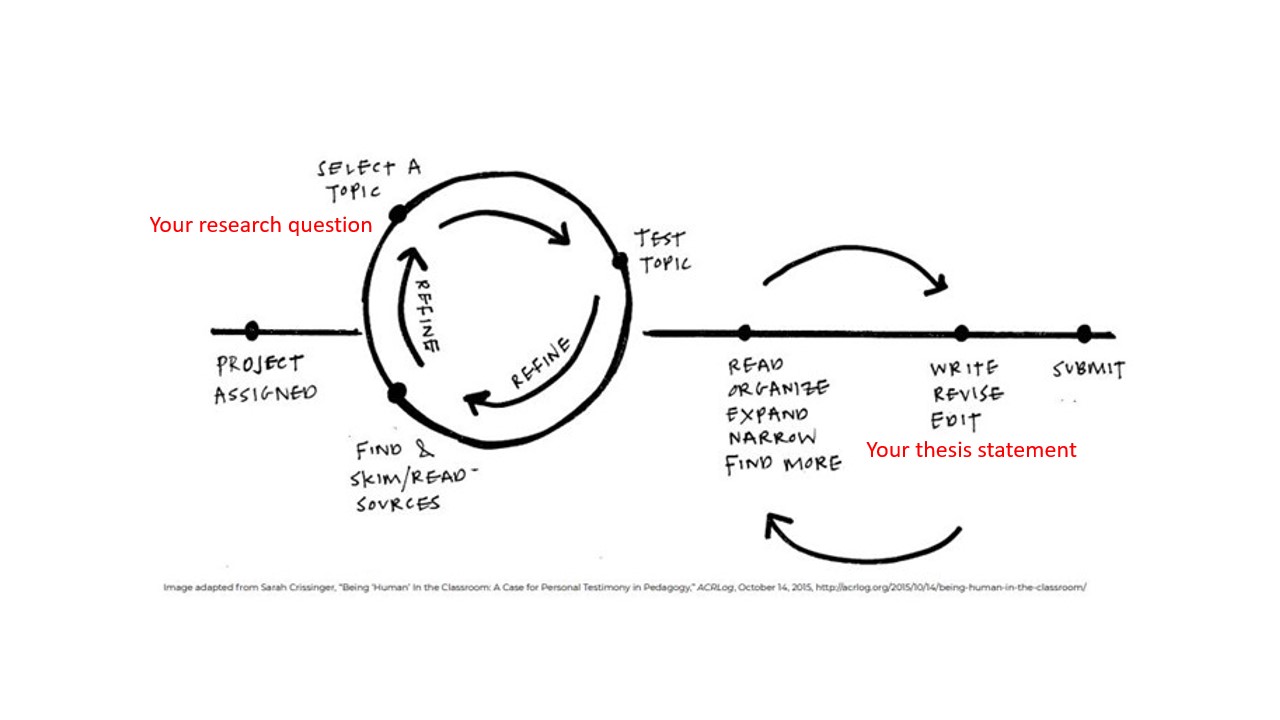

- Information you encounter at the beginning of the research process will help you refine your topic and questions.

- Take a second to think realistically about the information you’ll need to accomplish your task. You don’t need a peer-reviewed article to find out if praying mantises eat their mates, but you might if you want to find out why.

Ask Yourself

- Can you visualize the early phases of the research process: identifying a research topic and writing a thesis statement?

- What’s the last thing you looked up on Wikipedia? Did you stop when you found the information you needed, or did you click on another link and another link until you learned additional information about your topic?

- When was the last time you searched for multiple perspectives during the information gathering process?

- Were the topics you researched in the past too broad or too narrow?