Frame 5: Scholarship as Conversation

William Perrenod

What does “Scholarship as Conversation” mean?

Scholarship as conversation refers to the way scholars communicate with each other. Scholars identify varied sources of information, evaluate it, and when it is of value, incorporate it into their research projects. This is like a discussion you may have with a group of college friends that explores a subject. Your conversation could discuss varied perspectives on a topic, critically evaluate the contributions made by others, draw reasonable conclusions based on the interpretation of the shared information, and perhaps alter each other’s viewpoints.

Imagine that you enter a room and you’ve arrived late. In the corner of the room there are people already engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to stop and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps in the conversation that had gone before. You listen for a while until you decide that you understand the argument; and then, an opportunity opens, and you contribute your thoughts to the conversation. Someone answers you and you answer him, another comes to your defense, and another aligns himself against you. The discussion is endless. The hour grows late, and you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress (Burke, 1957).

General conversations with friends and scholarly conversations aren’t always pleasant, and they are not always linear; there isn’t always a clear line from beginning to an end. In fact, scholarly conversations can be circular and messy, and most of the time, they never end!

Picture the Scholarly Conversation

Picture a scholarly conversation as a bunch of well-informed curious people coming together to talk about something they all love and find interesting. Imagine people literally sitting around a big round table talking about ideas they’re all excited about and want to share with each other. Picture scholars exchanging thoughts and seeking feedback. Imagine those scholarly ideas being represented in articles and then published in journals. Then, imagine other scholars reading the articles and writing reviews that praise or criticize the ideas, the research, the theories, or the writing style. Lastly, visualize what happens when more and more scholars write and contribute articles to the conversation.

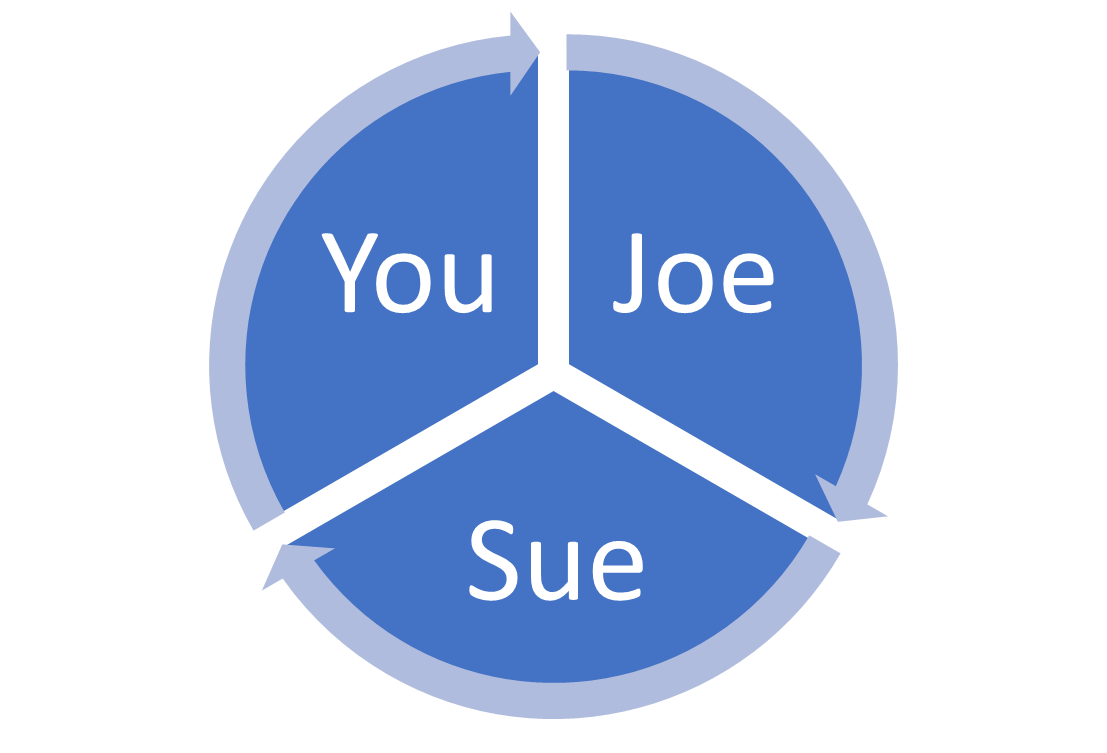

For example, if you wrote an article that examined social media and algorithms and then Joe wrote an article saying, “your article on social media and algorithms is garbage, here’s what I think about the topic,” you and Joe are now having a conversation. It may not be a fun conversation, but you are writing in response to one another about something you are both passionate about. Later, Sue comes along and writes an article that agrees with you but disagrees with Joe. Now you are involved in a three-way conversation. And the conversation just grows and grows as more people talk, write, or maybe just listen.

A scholarly conversation is about sharing, responding, and valuing one another’s work. For example, if Joe responds to the article you wrote on social media and algorithms, then he is going to cite you. If Sue then publishes an article that disproves of Joe’s article, she is going to cite Joe.

There are few reasons why Sue uses citations in her article:

- Even if Sue disagrees with Joe’s work, she respects that Joe put effort into it and his work has value. She also wants his work to be recognized.

- When Sue cites Joe, it also means anyone who jumps into the conversation later will be able to backtrack and catch-up with the entire conversation. Using Sues citations, anyone new to the conversation can trace the discussion back to Joe’s article and then trace that back to yours.

Sue’s article and her citations puts the entire conversation into context for the next person that writes an article on social media and algorithms.

Scholarly conversations evolve into circles, they don’t always follow a straight path, and sometimes they don’t follow a timely order. You may engage in a conversation with someone today, you can engage with someone who spoke ten years ago, or someone that started a conversation 100 years ago! You could jump into a scholarly conversation wherever you want. And if you do jump in, you could change the path of the conversation. Your contribution of a new discovery or a new point of view could drastically impact the way a subject is identified. Your involvement in a conversation could result in a reexamination of a topic and the discovery of a new path no one realized was available before

Have you ever entered a room only to hear a conversation? Sometimes it’s nice just to be among other people and appreciate what they have to say. Think of reading books and articles or listening to podcasts as engaging in a conversation too. It’s fine to simply want to listen.

The imagery of entering a conversation is nice because it’s inviting and less formal. And because of the Internet, you can enter and contribute to conversations in ways people 50 years ago never dreamed of! There are many blogs that provide opportunities for readers to engage and start a conversation, you may even participate in a conversation on Twitter! However, with any new conversation, you will probably listen a little at first, ask some questions, and then start giving your own opinions.

For example, if you were writing a research paper on social justice, you may want to participate in a conversation on Twitter related to homelessness. Some of the tweets may be important if they develop into a discussion that addresses why certain groups of people are marginalized within a particular society. You might even re-tweet a source of information on the injustices associated with homelessness and then tweet your own thoughts. A conversation like this could be of great value if it identifies additional topics associated with homelessness and if it encourages you to engage in activities that improve the circumstances of others.

The Takeaway

There is a lot to take away from this concept:

- Whenever you communicate you are engaging in a conversation.

- When you respond to the ideas of other scholars in your research papers, you’re really responding to the scholars themselves and including them in your conversation.

- Following citations, over centuries, can show the influence of an idea. Citations tell us where research began and where it might go in the future.

- Be respectful of other scholars’ work and their part in the conversation by citing them.

- Engage in scholarly conversations whenever you feel ready and in whatever platform you feel comfortable.

- Engage in open conversations. This means making sure information is available to those who want to listen and making sure we hear the voices that are at risk of being silenced.

Ask Yourself

- What scholarly conversations have you participated in recently? Is there a professor you enjoy talking to about their field of study?

- Do you follow a Facebook group that shares your scholarly interests? Do you contribute or just listen?

- Think of a scholarly conversation surrounding a topic.

- Whose voice is missing from the conversation and why do you think that is?