5.5-Microbial Growth Control

MICROBIAL GROWTH CONTROL

![Most environments, including cars, are not sterile. A study<a class="footnote" title="R.E. Stephenson et al. “Elucidation of Bacteria Found in Car Interiors and Strategies to Reduce the Presence of Potential Pathogens.”Biofouling 30 no. 3 (2014):337–346." id="return-footnote-187-1" href="#footnote-187-1" aria-label="Footnote 1"><sup class="footnote">[1]</sup></a> analyzed 11 locations within 18 different cars to determine the number of microbial colony-forming units (CFUs) present. The center console harbored by far the most microbes (506 CFUs), possibly because that is where drinks are placed (and often spilled). Frequently touched sites also had high concentrations.](https://open.oregonstate.education/app/uploads/sites/8/2019/06/Fig.-13.1.png)

Introduction

How clean is clean? People wash their cars and vacuum the carpets, but most would not want to eat from these surfaces. Similarly, we might eat with silverware cleaned in a dishwasher, but we could not use the same dishwasher to clean surgical instruments. As these examples illustrate, “clean” is a relative term. Car washing, vacuuming, and dishwashing all reduce the microbial load on the items treated, thus making them “cleaner.” But whether they are “clean enough” depends on their intended use. Because people do not normally eat from cars or carpets, these items do not require the same level of cleanliness that silverware does. Likewise, because silverware is not used for invasive surgery, these utensils do not require the same level of cleanliness as surgical equipment, which requires sterilization to prevent infection.

Why not play it safe and sterilize everything? Sterilizing everything we come in contact with is impractical, as well as potentially dangerous. As this chapter will demonstrate, sterilization protocols often require time- and labor-intensive treatments that may degrade the quality of the item being treated or have toxic effects on users. Therefore, the user must consider the item’s intended application when choosing a cleaning method to ensure that it is “clean enough.”

- R.E. Stephenson et al. “Elucidation of Bacteria Found in Car Interiors and Strategies to Reduce the Presence of Potential Pathogens.”Biofouling 30 no. 3 (2014):337–346. ↵

Controlling Microbial Growth

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between the various biological safety levels and explain methods used for handling microbes at each level

- Compare disinfectants, antiseptics, and sterilants

- Describe the principles of controlling the presence of microorganisms through sterilization and disinfection

To prevent the spread of human disease, it is necessary to control the growth and abundance of microbes in or on various items frequently used by humans. Inanimate items, such as doorknobs, toys, or towels, which may harbor microbes and aid in disease transmission, are called fomites. Two factors heavily influence the level of cleanliness required for a particular fomite and, hence, the protocol chosen to achieve this level. The first factor is the application for which the item will be used. For example, invasive applications that require insertion into the human body require a much higher level of cleanliness than applications that do not. The second factor is the level of resistance to antimicrobial treatment by potential pathogens. For example, foods preserved by canning often become contaminated with the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, which produces the neurotoxin that causes botulism. Because C. botulinum can produce endospores that can survive harsh conditions, extreme temperatures and pressures must be used to eliminate the endospores. Other organisms may not require such extreme measures and can be controlled by a procedure such as washing clothes in a laundry machine.

Laboratory Biological Safety Levels

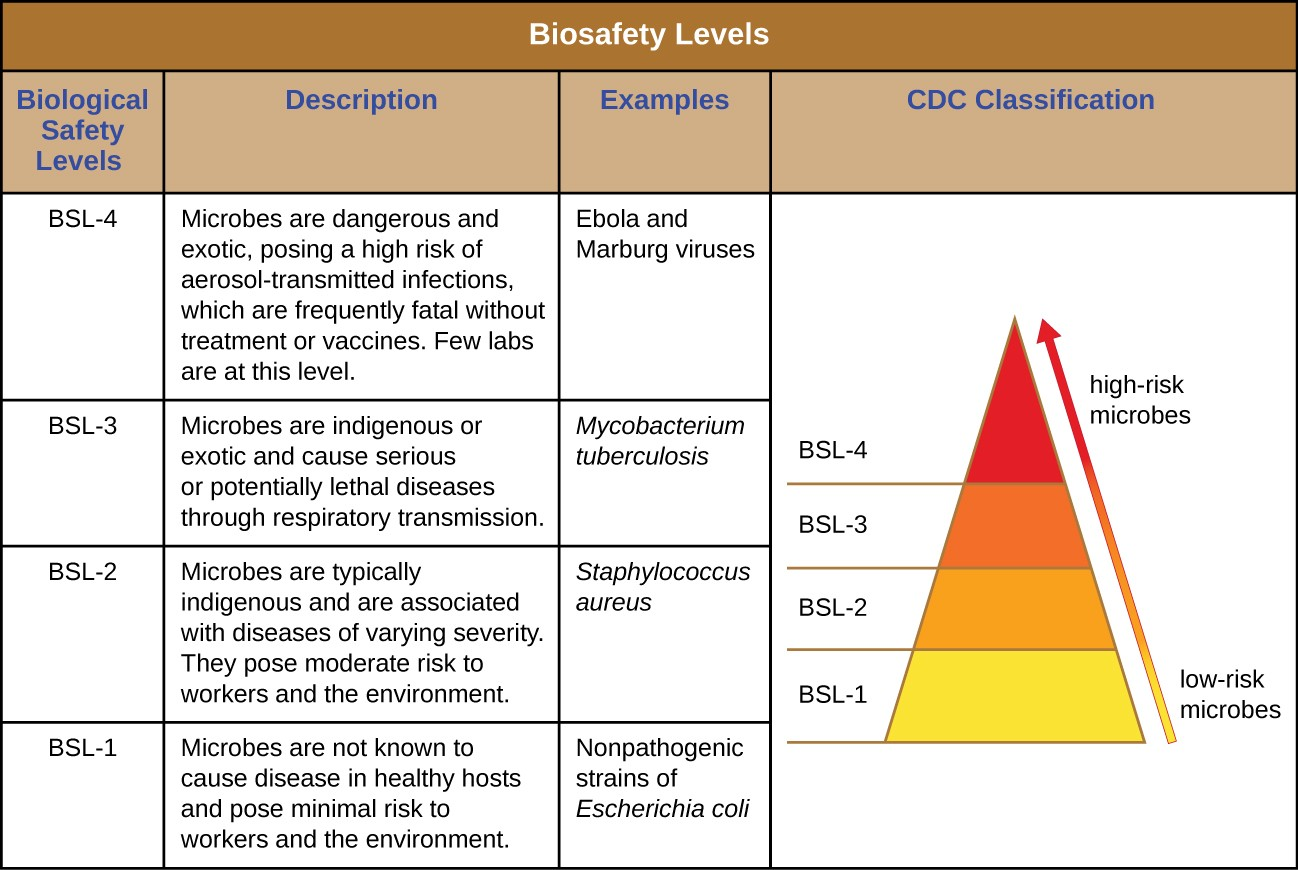

For researchers or laboratory personnel working with pathogens, the risks associated with specific pathogens determine the levels of cleanliness and control required. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) have established four classification levels, called “biological safety levels” (BSLs). Various organizations around the world, including the World Health Organization (WHO) and the European Union (EU), use a similar classification scheme. According to the CDC, the BSL is determined by the agent’s infectivity, ease of transmission, and potential disease severity, as well as the type of work being done with the agent.[1]

Each BSL requires a different level of biocontainment to prevent contamination and spread of infectious agents to laboratory personnel and, ultimately, the community. For example, the lowest BSL, BSL-1, requires the fewest precautions because it applies to situations with the lowest risk for microbial infection.

BSL-1 agents are those that generally do not cause infection in healthy human adults. These include noninfectious bacteria, such as nonpathogenic strains of Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis, and viruses known to infect animals other than humans, such as baculoviruses (insect viruses). Because working with BSL-1 agents poses very little risk, few precautions are necessary. Laboratory workers use standard aseptic technique and may work with these agents at an open laboratory bench or table, wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) such as a laboratory coat, goggles, and gloves, as needed. Other than a sink for handwashing and doors to separate the laboratory from the rest of the building, no additional modifications are needed.

Agents classified as BSL-2 include those that pose moderate risk to laboratory workers and the community, and are typically “indigenous,” meaning that they are commonly found in that geographical area. These include bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella spp., and viruses like hepatitis, mumps, and measles viruses. BSL-2 laboratories require additional precautions beyond those of BSL-1, including restricted access; required PPE, including a face shield in some circumstances; and the use of biological safety cabinets for procedures that may disperse agents through the air (called “aerosolization”). BSL-2 laboratories are equipped with self-closing doors, an eyewash station, and an autoclave, which is a specialized device for sterilizing materials with pressurized steam before use or disposal. BSL-1 laboratories may also have an autoclave.

BSL-3 agents have the potential to cause lethal infections by inhalation. These may be either indigenous or “exotic,” meaning that they are derived from a foreign location, and include pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus anthracis, West Nile virus, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Because of the serious nature of the infections caused by BSL-3 agents, laboratories working with them require restricted access. Laboratory workers are under medical surveillance, possibly receiving vaccinations for the microbes with which they work. In addition to the standard PPE already mentioned, laboratory personnel in BSL-3 laboratories must also wear a respirator and work with microbes and infectious agents in a biological safety cabinet at all times. BSL-3 laboratories require a hands- free sink, an eyewash station near the exit, and two sets of self-closing and locking doors at the entrance. These laboratories are equipped with directional airflow, meaning that clean air is pulled through the laboratory from clean areas to potentially contaminated areas. This air cannot be recirculated, so a constant supply of clean air is required.

BSL-4 agents are the most dangerous and often fatal. These microbes are typically exotic, are easily transmitted by inhalation, and cause infections for which there are no treatments or vaccinations. Examples include Ebola virus and Marburg virus, both of which cause hemorrhagic fevers, and smallpox virus. There are only a small number of laboratories in the United States and around the world appropriately equipped to work with these agents. In addition to BSL-3 precautions, laboratory workers in BSL-4 facilities must also change their clothing on entering the laboratory, shower on exiting, and decontaminate all material on exiting. While working in the laboratory, they must either wear a full-body protective suit with a designated air supply or conduct all work within a biological safety cabinet with a high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA)-filtered air supply and a doubly HEPA-filtered exhaust. If wearing a suit, the air pressure within the suit must be higher than that outside the suit, so that if a leak in the suit occurs, laboratory air that may be contaminated cannot be drawn into the suit (Figure 5.18). The laboratory itself must be located either in a separate building or in an isolated portion of a building and have its own air supply and exhaust system, as well as its own decontamination system. The BSLs are summarized in Figure 5.19.

Link to Learning

To learn more (https://openstax.org/l/22cdcfourbsls) about the four BSLs, visit the CDC’s website.

- What are some factors used to determine the BSL necessary for working with a specific pathogen?

Sterilization

The most extreme protocols for microbial control aim to achieve sterilization: the complete removal or killing of all vegetative cells, endospores, and viruses from the targeted item or environment. Sterilization protocols are generally reserved for laboratory, medical, manufacturing, and food industry settings, where it may be imperative for certain items to be completely free of potentially infectious agents. Sterilization can be accomplished through either physical means, such as exposure to high heat, pressure, or filtration through an appropriate filter, or by chemical means. Chemicals that can be used to achieve sterilization are called sterilants. Sterilants effectively kill all microbes and viruses, and, with appropriate exposure time, can also kill endospores.

For many clinical purposes, aseptic technique is necessary to prevent contamination of sterile surfaces. Aseptic technique involves a combination of protocols that collectively maintain sterility, or asepsis, thus preventing contamination of the patient with microbes and infectious agents. Failure to practice aseptic technique during many types of clinical procedures may introduce microbes to the patient’s body and put the patient at risk for sepsis, a systemic inflammatory response to an infection that results in high fever, increased heart and respiratory rates, shock, and, possibly, death. Medical procedures that carry risk of contamination must be performed in a sterile field, a designated area that is kept free of all vegetative microbes, endospores, and viruses. Sterile fields are created according to protocols requiring the use of sterilized materials, such as packaging and drapings, and strict procedures for washing and application of sterilants. Other protocols are followed to maintain the sterile field while the medical procedure is being performed.

One food sterilization protocol, commercial sterilization, uses heat at a temperature low enough to preserve food quality but high enough to destroy common pathogens responsible for food poisoning, such as C. botulinum. Because botulinum and its endospores are commonly found in soil, they may easily contaminate crops during harvesting, and these endospores can later germinate within the anaerobic environment once foods are canned. Metal cans of food contaminated with C. botulinum will bulge due to the microbe’s production of gases; contaminated jars of food typically bulge at the metal lid. To eliminate the risk for C. botulinum contamination, commercial food-canning protocols are designed with a large margin of error. They assume an impossibly large population of endospores (1012 per can) and aim to reduce this population to 1 endospore per can to ensure the safety of canned foods. For example, low- and medium-acid foods are heated to 121 °C for a minimum of 2.52 minutes, which is the time it would take to reduce a population of 1012 endospores per can down to 1 endospore at this temperature. Even so, commercial sterilization does not eliminate the presence of all microbes; rather, it targets those pathogens that cause spoilage and foodborne diseases, while allowing many nonpathogenic organisms to survive. Therefore, “sterilization” is somewhat of a misnomer in this context, and commercial sterilization may be more accurately described as “quasi-sterilization.”

- What is the difference between sterilization and aseptic technique?

Other Methods of Control

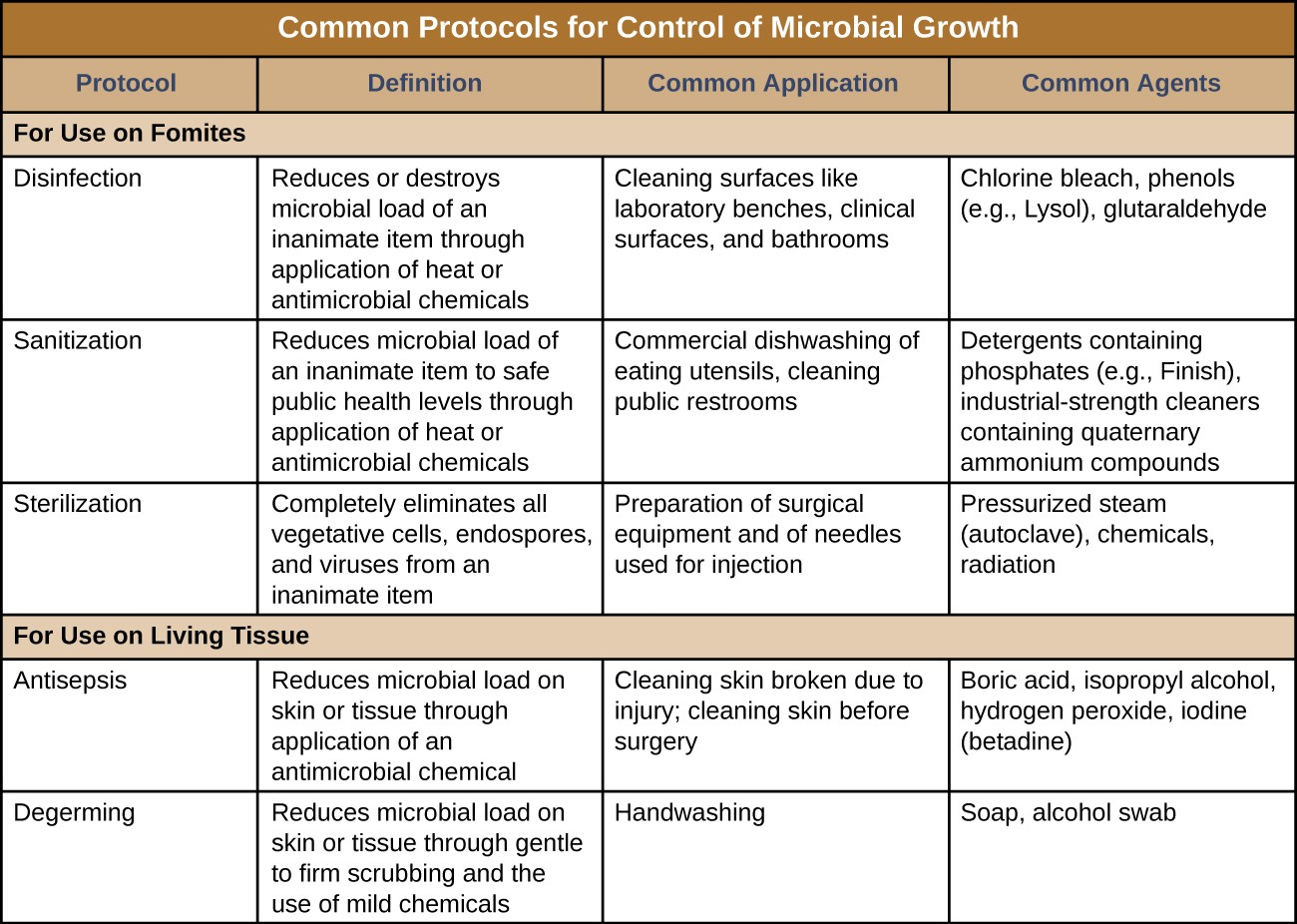

Sterilization protocols require procedures that are not practical, or necessary, in many settings. Various other methods are used in clinical and nonclinical settings to reduce the microbial load on items. Although the terms for these methods are often used interchangeably, there are important distinctions (Figure 5.20).

The process of disinfection inactivates most microbes on the surface of a fomite by using antimicrobial chemicals or heat. Because some microbes remain, the disinfected item is not considered sterile. Ideally, disinfectants should be fast acting, stable, easy to prepare, inexpensive, and easy to use. An example of a natural disinfectant is vinegar; its acidity kills most microbes. Chemical disinfectants, such as chlorine bleach or products containing chlorine, are used to clean nonliving surfaces such as laboratory benches, clinical surfaces, and bathroom sinks. Typical disinfection does not lead to sterilization because endospores tend to survive even when all vegetative cells have been killed.

Unlike disinfectants, antiseptics are antimicrobial chemicals safe for use on living skin or tissues. Examples of antiseptics include hydrogen peroxide and isopropyl alcohol. The process of applying an antiseptic is called antisepsis. In addition to the characteristics of a good disinfectant, antiseptics must also be selectively effective against microorganisms and able to penetrate tissue deeply without causing tissue damage.

The type of protocol required to achieve the desired level of cleanliness depends on the particular item to be cleaned. For example, those used clinically are categorized as critical, semicritical, and noncritical. Critical items must be sterile because they will be used inside the body, often penetrating sterile tissues or the bloodstream; examples of critical items include surgical instruments, catheters, and intravenous fluids. Gastrointestinal endoscopes and various types of equipment for respiratory therapies are examples of semicritical items; they may contact mucous membranes or nonintact skin but do not penetrate tissues. Semicritical items do not typically need to be sterilized but do require a high level of disinfection. Items that may contact but not penetrate intact skin are noncritical items; examples are bed linens, furniture, crutches, stethoscopes, and blood pressure cuffs. These articles need to be clean but not highly disinfected.

The act of handwashing is an example of degerming, in which microbial numbers are significantly reduced by gently scrubbing living tissue, most commonly skin, with a mild chemical (e.g., soap) to avoid the transmission of pathogenic microbes. Wiping the skin with an alcohol swab at an injection site is another example of degerming. These degerming methods remove most (but not all) microbes from the skin’s surface.

The term sanitization refers to the cleansing of fomites to remove enough microbes to achieve levels deemed safe for public health. For example, commercial dishwashers used in the food service industry typically use very hot water and air for washing and drying; the high temperatures kill most microbes, sanitizing the dishes. Surfaces in hospital rooms are commonly sanitized using a chemical disinfectant to prevent disease transmission between patients. Figure 9.4 summarizes common protocols, definitions, applications, and agents used to control microbial growth.

![]()

- What is the difference between a disinfectant and an antiseptic?

- Which is most effective at removing microbes from a product: sanitization, degerming, or sterilization? Explain.

Measuring Microbial Control

Physical and chemical methods of microbial control that kill the targeted microorganism are identified by the suffix -cide (or -cidal). The prefix indicates the type of microbe or infectious agent killed by the treatment method: bactericides kill bacteria, while viricides kill or inactivate viruses. Other methods do not kill organisms but, instead, stop their growth, making their population static; such methods are identified by the suffix-stat (or -static). For example, bacteriostatic treatments inhibit the growth of bacteria. Factors that determine whether a particular treatment is -cidal or -static include the types of microorganisms targeted, the concentration of the chemical used, and the nature of the treatment applied.

Although -static treatments do not actually kill infectious agents, they are often less toxic to humans and other animals, and may also better preserve the integrity of the item treated. Such treatments are typically sufficient to keep the microbial population of an item in check. The reduced toxicity of some of these -static chemicals also allows them to be impregnated safely into plastics to prevent the growth of microbes on these surfaces. Such plastics are used in products such as toys for children and cutting boards for food preparation. When used to treat an infection, -static treatments are typically sufficient in an otherwise healthy individual, preventing the pathogen from multiplying, thus allowing the individual’s immune system to clear the infection.

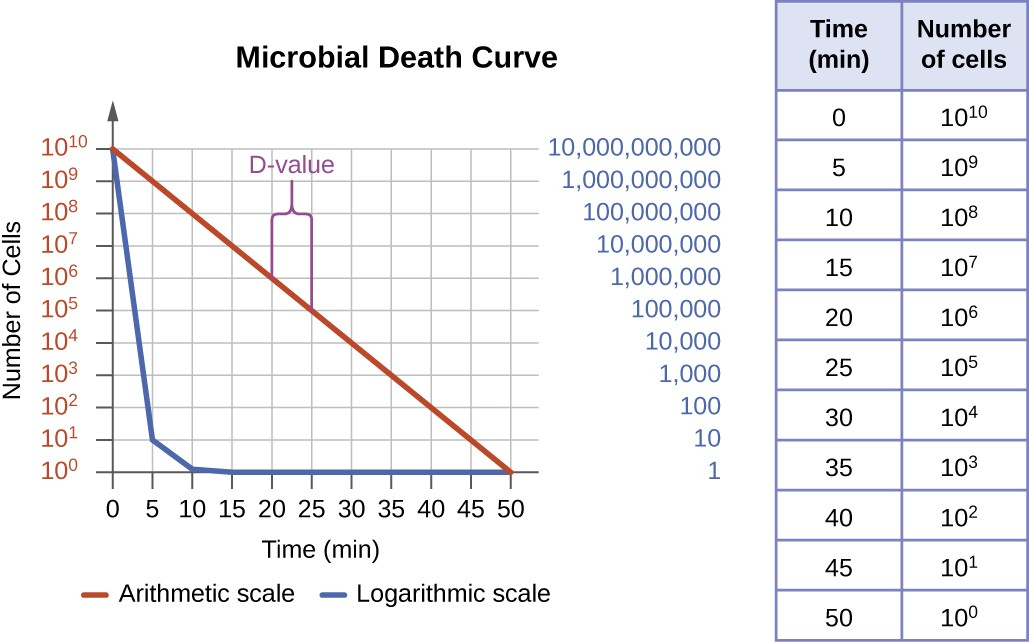

The degree of microbial control can be evaluated using a microbial death curve to describe the progress and effectiveness of a particular protocol. When exposed to a particular microbial control protocol, a fixed percentage of the microbes within the population will die. Because the rate of killing remains constant even when the population size varies, the percentage killed is more useful information than the absolute number of microbes killed. Death curves are often plotted as semilog plots just like microbial growth curves because the reduction in microorganisms is typically logarithmic (Figure 5.21). The amount of time it takes for a specific protocol to produce a one order- of-magnitude decrease in the number of organisms, or the death of 90% of the population, is called the decimal reduction time (DRT) or D-value.

Several factors contribute to the effectiveness of a disinfecting agent or microbial control protocol. First, as demonstrated in Figure 5.21, the length of time of exposure is important. Longer exposure times kill more microbes. Because microbial death of a population exposed to a specific protocol is logarithmic, it takes longer to kill a high-population load than a low-population load exposed to the same protocol. A shorter treatment time (measured in multiples of the D-value) is needed when starting with a smaller number of organisms. Effectiveness also depends on the susceptibility of the agent to that disinfecting agent or protocol. The concentration of disinfecting agent or intensity of exposure is also important. For example, higher temperatures and higher concentrations of disinfectants kill microbes more quickly and effectively. Conditions that limit contact between the agent and the targeted cells cells—for example, the presence of bodily fluids, tissue, organic debris (e.g., mud or feces), or biofilms on surfaces—increase the cleaning time or intensity of the microbial control protocol required to reach the desired level of cleanliness. All these factors must be considered when choosing the appropriate protocol to control microbial growth in a given situation.

- What are two possible reasons for choosing a bacteriostatic treatment over a bactericidal one?

- Name at least two factors that can compromise the effectiveness of a disinfecting agent.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Recognizing the Biosafety Levels.” http://www.cdc.gov/training/quicklearns/biosafety/. Accessed June 7, 2016. ↵

- R.E. Stephenson et al. “Elucidation of Bacteria Found in Car Interiors and Strategies to Reduce the Presence of Potential Pathogens.” Biofouling 30 no. 3 (2014):337–346. ↵