2. Atmosphere and Weather

Controls of Global Temperature

The term temperature control is used to describe something that, when it increases or decreases, is associated with an increase or decrease in average annual temperature, and/or the seasonal variation in temperature. There are several other controls on temperature but the three most important are latitude, land-water heating differences.

Latitude

Several controlling factors determine global temperatures. The first and most significant is latitude. Because of the Earth’s shape and the sun’s angle hitting the planet, temperatures are highest near the equator and decrease toward the poles. In fact, at the equator, more energy is absorbed from the sun than is radiated back into space. At the poles, more energy is radiated back into space than is absorbed by the sun.

Because of the tilt of Earth’s axis, day lengths vary with seasons at higher latitudes. Equatorial regions have nearly 12 hours of daylight all year, but far north and south regions experience extremely long days in their summers and short days in their winters, respectively. The result is that high latitudes experience colder average temperatures for the year, with a large difference between winter and summer temperatures.

Land-Water Heating

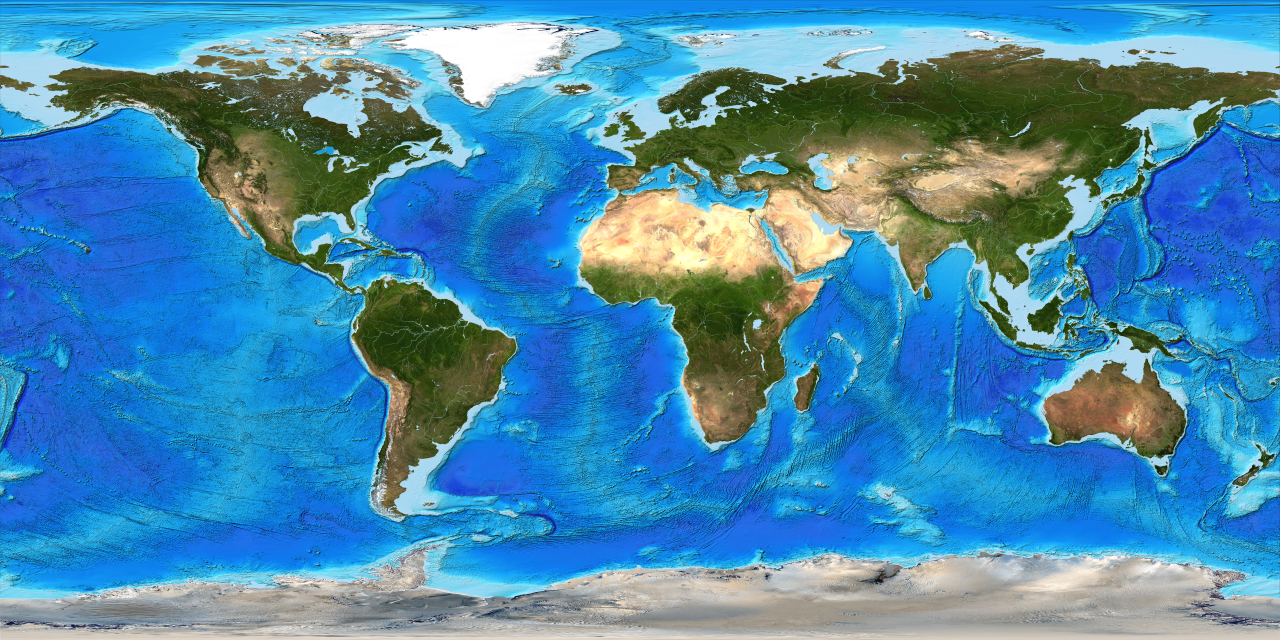

The next control on temperature is the distribution of land vs. water on the planet. Places near the ocean tend to have milder climates year-round versus regions surrounded by land. This is because the earth can heat up and cool down faster and with more significant fluctuation than the ocean. One reason is that sunlight must heat a larger volume in the ocean because light can pass through water. Also, water requires five times more energy to warm one degree Celsius than the same amount of land, a characteristic called specific heat. Thus, temperatures in places near large bodies of water change slowly compared to temperatures surrounded by land. This is why places in the middle of continents have hotter summers and colder winters than places at the same latitude near the ocean. Ocean currents are also vital controls in transferring heat around the planet. In the Northern Hemisphere, ocean currents rotate clockwise, bringing cold water from the North Pole toward the equator and warm water from the equator toward the North Pole. The opposite occurs in the Southern Hemisphere, where ocean currents rotate counterclockwise.

Elevation

The last control of temperature is elevation. On average, atmospheric temperature decreases 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit per 1,000 feet rise in elevation (6.5 °C per 1,000 meters). This is called the normal lapse rate or also called the standard temperature lapse rate.

Sunset on Kilimanjaro. At 19,341 feet high and with more than 10,000 feet of local relief, the slopes of Kilimanjaro make a powerful demonstration of the effects of altitude on temperature. The lower plains have tropical warmth while the summit is covered in snow and ice year-round. 2012 photo by Tim Scharks.