1 Chapter 1 – How Do We Know What We Know?

1.1 – Novel Problems Require An Open Mind and Experimentation

Nothing that has ever been developed has occurred without patiently experiencing what is happening, and then experimenting to see if what we thought was happening is, in fact, happening. When we first come across something that we’re unfamiliar with, we experience it, and then we ask questions which we try to answer by setting up some type of experiment. The questions that we ask help us to know what type of experiment to perform. The experiment might only be a quick check of facts or a review of what we thought we experienced. Really, this is a very natural thing that humans do. We do this type of process all the time. We just need to be aware of this process so that we can develop it into a more powerful engine of discovery.

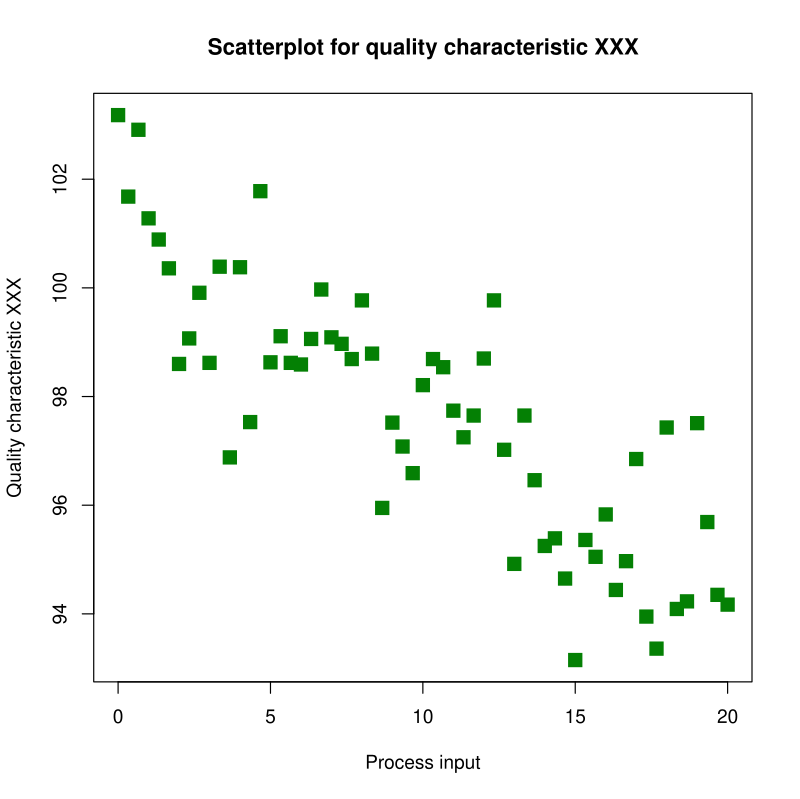

Here are three images. Write three questions for each of the three images. The questions can be whatever comes to mind as you view the images.

Here’s a video of a song. Please listen to it and then write three questions about what you heard. The questions can be whatever comes to mind as you listen to the music.

1.2 – Learn By Exploring

1) Think back to a time when you first had to fix something. Maybe it was your bicycle, or your car, or heater, or a door, or a phone, or anything that you needed to fix. In the field below, make note of what it was it that needed fixing.

2) Write a short description of how you approached the problem (what did you do to fix it?).

3) When trying to fix it, what did you learn? Write a short description of what it was that you learned.

4) Now, think about a later time when you had to fix another problem. Did the first problem come to mind when you thought about fixing the new problem (yes or no)?

5) If the earlier problem came to mind when you tried to solve the later problem, did it help? (If the problem had nothing to do with the earlier problem, then just write N/A)

6) If the later problem had nothing to do with the earlier problem, what did you do to fix the later problem?

7) Now, think about your lifetime of dealing with different types of problems, can you describe any pattern of how you’ve learned to deal with those problems?

8) Have the patterns that you’ve learned to use to solve problems helped you with school (yes or no)?

9) If those patterns helped you, describe how they helped (if not, put N/A).

10) If those patterns didn’t help, describe why they didn’t help (if they helped, put N/A).

Learning is about exploring and trying new things as well as those things we already know. When we’re confronted with unfamiliar things, we think about what we already know. If we can apply a previous process successfully, then that will suffice. However, when the demand for a new process confronts us, we need to learn about it in a manner similar to how we learned other things in the past. It’s this meta-process, a basic process applicable in most circumstances, that lets us get beyond where we’re at and solve unfamiliar problems.

Often, we need to look up information to solve problems. Learning to find what we need is a very useful skill. However, just finding answers that exist on the internet or elsewhere will not always be sufficient to get the answers we need. This is when we need to explore.

As an example, when we’re using a program like Word or Excel, we often need to look things up at first. Once we know the layout of the program, we can use our knowledge of the overall structure to find functions that control what we need. Just knowing that drop-down menus give us options for what we can do gives us a start on how to get where we need to be within a program. After we’ve used a few different programs and apps, we start to notice a pattern of how these programs and apps are designed and how they work. When we do this, we’re using what we have learned, but until we’ve explored and looked things up we won’t have this knowledge.

At our college, we use Canvas and ctcLink. At first we might find these programs confusing, but as we explore them, we learn how to use them. Some instructors have a lot of different items that need to be done for the class, and sometimes knowing what to do next or how to do it can be confusing. We can explore the course by clicking on various buttons and links to see what they do or where they take us. Doing this helps us become more confident of working in different environments. Of course, we should contact our instructor for clarification if, after a few tries, we are still unsure.

When we explore, noticing details that bear upon what we need to know helps us to discover new possibilities. For example, when we are faced with finding a new route to avoid traffic, we can look at a map and see the possible routes and, hopefully, find a route that will work well. Another example of noticing details can happen when we listen to music. The different instruments playing different parts can be heard separately and together. When we look at a picture, there are often many details to notice.

Finally, exploring requires time and energy. When we’re out of time or energy, we should contact the instructor to let them know that we need a bit more time to complete an assignment or project. Most instructors are flexible because they know that work and family and emergencies can get in the way of successfully completing the assignment or project. So, communicating with your instructor is very important. It helps them to help you.

For each of the images below, explain what you notice about the image that helped you understand it or solve it:

Image 1 – Maze

Image 2 – Scatterplot

Image 3 – Letters

OTTFFSSENT

1.3 – How To Ask A Good Question

Learning is not just about reading or having someone explain something, it’s often about asking questions. Asking questions which are clear and complete leads us to the answers we need. For example, if we ask “How often do people use social media?”, it’s not clear who the “people” we’re referring to are, or what “often” means. It also doesn’t specify if the social media is being accessed on a mobile device or on a laptop. If that’s of interest to the person asking the question, then it should be included in the question.

Have you ever had someone ask you a question, and you weren’t sure of what the question was referencing? This happens because the person asking the question assumes that you know what they’re referring to, or they forget to include what the question is referencing. Suppose your friend asks you “Where did she go?”. You might ask them “Where did who go?”. “Janelle”. “Oh, she went home”.

Sometimes, a question is ambiguous. This means that there could be more than one way to interpret the meaning. Example: “Where’s the homework due on Wednesday?”. Is this asking the location of the homework? The place it’s to be submitted?

Here’s a way to check to see if the question you asked is clear, complete, and unambiguous.

1) Make a list of all the words in the question:

How

Often

Do

People

Use

Social media

2) Think about what each word is supposed to mean in the context of what you’re asking:

How –

Often – Daily? Weekly? Monthly? Ever?

Do – When? Now? 6 months ago? In the past year?

People – Which people? Which location? Renton? King County?, Washington State? How old are they?

Use – Use for any purpose? For entertainment? For messaging? For live streaming?

Social media – Any social media? Does this include sites like Reddit or blogs?

3) Jot down any words that clarify what each of the words in your original question intend to ask:

How –

Often – Weekly

Do – In the past week

People – Adults ages 21-30 in King County, WA

Use – For entertainment

Social media – Social media websites, but not sites like Reddit or blogs.

4) Rewrite the question using all the words that help to clarify the question. You don’t need to use every word from the list, just the words that make the question clear, complete, and unambiguous. The order of the words can change to make the question easier to understand:

“In the past week, how many times has the typical adult 21-30 years old living in King County WA used a social media website like Facebook or TikTok, but not sites like Reddit or a blog?”

One of the many benefits of creating a clear, complete, and unambiguous question is that doing so can sometimes lead to an answer. When we ask questions that need data to help us estimate some quantity, a good question will allow us to collect the data needed to answer it. Consider the following question:

“In the past week, how many times has the typical adult 21-30 years old living in King County WA used a social media website like Facebook or TikTok, but not sites like Reddit or a blog?”

For the above question, we can get a random sample of responses from 21-30 year old adults living in King County WA. Perhaps we can conduct the survey by phone or in person at some location that would give us a representative sample.

When we ask a question about why something works the way it does (like a math problem), the more clearly and completely we create the question, the more likely it is that the answer will occur to us. Consider the following question:

“How do we solve for the unknown quantity x?”

How – Is there a method?

Do –

We – Is there a way that I can do this aside from what I might have been shown? Is there a similar problem that I can use to help me with this?

Solve – What does it mean to solve this?

(Equation) – This is an equation because it has an ‘equal’ sign.

For –

The –

Unknown – Is it always unknown? Or is x a place-holder for some number that makes the equation a true statement?

Quantity – Is ‘Quantity’ only a number? Or are there units attached to the number?

With the original question broken down into more precise terms, we can reason that the unknown value x represents the quantity that would make the equation a true statement. We can try different methods of finding the value of x that works (solve the equation), perhaps by guessing and checking, or better yet, by using the process of algebra to quickly find the exact answer.

(Please note: This quarter we won’t do the posting board mentioned below. Instead, please write the question to yourself. In other words, choose an article, and then pretend that you’re another person asking questions about that article using the process this section has developed.) In the following posting board, please post a link to an article of interest to you and say why you chose it. Then, look at the articles that the other students have posted, and find at least one article that you think is interesting. Then, using the process that this section has developed, write a question to the person who posted the article. The question should be about the article. You might find this exercise a bit unusual because we are often only interested in answers. However, asking good questions gives us more than answers, it can lead us to unexpected discoveries.

1.4 – Does The Answer Make Sense?

When we submit an answer to a question, we must always ask ourselves “Does the answer make sense?”

For example, if we’re asked to find the probability of some event, and we get an answer of 2.5 for the probability, we should be careful to recognize that 2.5 is not a probability value because probabilities take values greater than or equal to zero, and less than or equal to 1 (alternatively 0% to 100%, inclusive).

Another example would be when we get a number which doesn’t make sense in the context of the question. Suppose we’re asked to find someone’s age, and we report the age as 365 years. This is not a reasonable value for an age of a human at this point in time.

Here’s another example which applies to safety. The drug Valium is a benzodiazepine that is used for anxiety, and a typical dose is in the range of 2 to 10 mg two to four times daily. If we get an answer that has 200 mg of Valium four times a day, we could be making a lethal error. Always check and recheck when it comes to safety.

1.5 – Artificial Intelligence (AI)

A machine that can produce answers in a conversational manner or code based on textual commands (ChatGPT), or create pictures based on descriptions (DALL-E), or can move like a human or an animal (robots) is said be be a type of artificial intelligence. We now live in an age where artificial intelligence (AI) is capable of generating information as if it were a person answering your question or request. This is a very big jump from simply using a search engine like Google. This might make us believe that we no longer need to learn because we can get any answer, create code, or create a picture simply by typing or speaking the query or commands. This is far from the the truth! It most likely will never be the case that humans will not need to learn or do the work required to learn, because machines are a product of the human mind and will, most likely, not exceed the creative capacity of the human mind. Even if machines eventually become sentient and sapient, humans would still need to learn. In fact, humans would need to adapt and learn much more than they do now.

Also, just like humans, AI can make mistakes. We can’t just accept anything that a machine tells us.

So, it is very important that we learn how to use AI in a way which helps us to learn. The good news is that we can easily learn to use it to help us learn.

Think of anything that you would like to know. Ask ChatGPT a question, and see if the answer you get makes sense. If it doesn’t make sense, ask it why it gave you the answer it did, or ask it for clarification. If you ask for clarification, give it a specific question that you feel will help clarify what it says. You can ask as many questions as you like. Please copy and paste the entire ChatGPT conversation into the field below. You will need to create an account on the ChatGPT website. It will ask for your phone number. If you would rather avoid giving your phone number to OpenAI (the company that makes ChatGPT), then you don’t have to do this exercise.

What do you think about your experience asking ChatGPT a question and then asking it follow-up questions?

Do you feel like you learned anything from it? If so, what did you learn?

Did what you learn give you any ideas about what you might be able to do for yourself or others?

Did this lead to other questions? If so, what were they?

1.6 – Making A Weekly Plan To Help Us Succeed

Making a table of days and hours in the day for when we will do the work for each class is a very useful thing to do. Here’s how it’s done.

Using a big piece of paper which you can tape to a wall, create a table like the one below with days of the week in the first column, and the hours of a day in the first row. Then decide on a task for each hour of the day, and for each day of the week. I’ve filled in just the tasks for Monday, but you should think about what you need to do each day of the week. Don’t worry about appointments that need to be scheduled as they are needed. Just get the basic pattern of activities for each day of the week.

By making a table like this you will discover that it takes much of the stress out of your week because you can easily see what needs to be done at any time during the week.

Keep a separate calendar for due dates and appointments. This table is to let you know which task should be done at any time during a day for which you have no other appointments or obligations.

| 0 (Midnight)… | 5am | 6am | 7am | |

| M | Sleep | Wake/Meditate | Eat | Statistics |

| T | Sleep | Wake/Meditate | Eat | Statistics |

| W | Sleep | Wake/Mediate | Eat | Biology |

| Th | Sleep | Wake/Meditate | Eat | Chemistry |